Increasing the equitable briefing of barristers

On 18 June 2016, the Law Council of Australia amended its Equitable Briefing Policy by introducing measurable targets and reporting mechanisms. The new goals are to have 20 per cent of all briefs or the value of briefs going to women barristers by 1 July 2018. The target is 30 per cent for senior counsel briefs. Very recently, big corporates such as Telstra, Woolworths and Westpac, and the majority of top-tier law firms (Allens, Herbert Smith Freehills, King & Wood Mallesons, Minter Ellison and Clayton Utz) made commitments to adopt the policy. In this post, we dive into Litimetrics’ datasets to look at the profile of the pool of barristers and current firm briefing practices so that we can analyse how achievable the targets are, and also look at tangible steps law firms and organisations can take to achieve the targets.

Before we do so, here are some caveats:

- we think the policy is a great step forward for the legal industry as a whole, despite any opinion we express about difficulty in meeting the targets

- there is some noisiness in the data, so don’t bet your house on these figures

- the figures include members of all state bar associations, but do not include those in the ACT and NT

- the data presented below about appearances is limited to data from the Supreme Courts in NSW and Victoria, the respective appellate courts of those states and the Federal Court up to the High Court.

Supply side: current makeup of the pool of barristers

The first step in answering the question of what the landscape will look like in July 2018 (about a year and a half away from the date of this post) is looking at the landscape now. There are obviously many more male barristers than female — our count is about 4,000 to 1,300 or just over 3 to 1. When looking at senior counsel only, that ratio blows out to just under 8 to 1 (in other words, only about 11% of senior counsel are females).

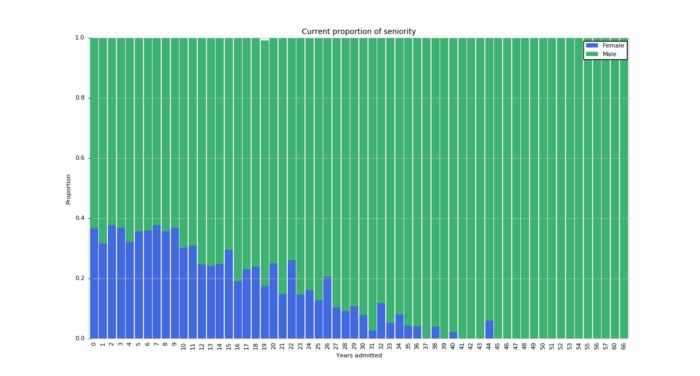

The proportion of male to females increases with the seniority of barristers, and although is more balanced at the very junior ranks, it’s still not even.

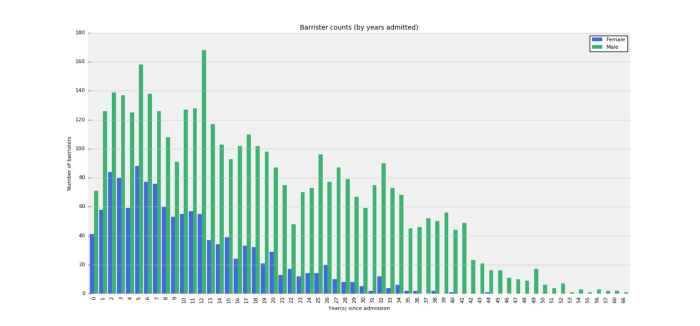

Looking at the chart below, and assuming admission and drop-off rates stay much the same, it seems unlikely that there’ll be a marked increase in the number of female barristers between now and the target date 1.5 years away. This is despite worthy measures to appoint a greater proportion of women as senior counsel and to encourage interest in joining the bar.

Each additional year of seniority results in a reduction in the number of barristers, but the dropoff rate is largely the same for both men and women

Again, looking at senior counsel, unless there’s a drastic change in the promotion of female juniors, 1.5 years will do little to the make up of the senior counsel pool. As the chart below shows, although there is greater balance between recently promoted senior counsel, the numbers are still not even. (We note that recent promotion rates seem to match the proportion of barristers at the level of seniority.)

../images/0c9QxILOVqV18MGW.png

There are a lot more male senior counsel than female, though the ratios are improving

Will the current proportions of barristers make it difficult to achieve the 20 per cent and 30 per cent targets? Looking at senior counsel, the 11 per cent of female senior counsel will be expected to take on about 30 per cent of all briefs. Whether this is possible depends on the current capacity of those barristers. If only a small proportion of barristers do most of the work, then it’s possible that the 11 per cent have capacity to take on a greater share of the work. What will happen in that event, is a transfer of work from one set of barristers (male senior counsel) to another (female senior counsel). On the other hand, if those barristers are ‘jammed’ (a phrase barristers use when they don’t want to take your work), then there isn’t going to be enough female barristers to do the work.

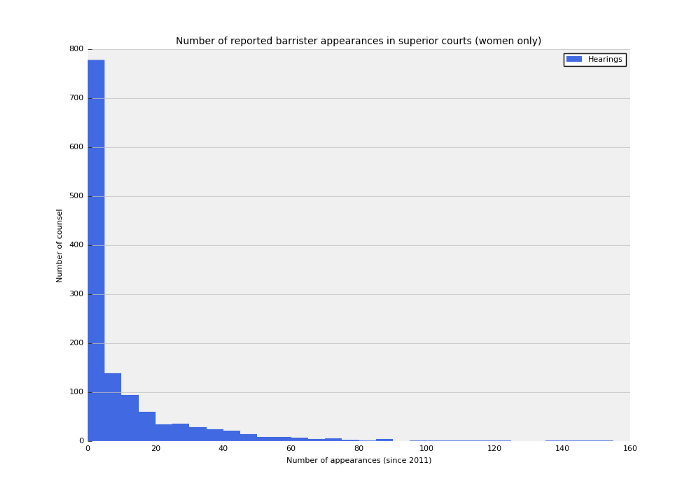

The following chart, which depicts the number of appearances by female barristers in the past five years, supports the hypothesis that the existing pool of female barristers can absorb a much greater number of briefs. The overwhelming majority of female barristers appeared less than 20 times in that five year period. Assuming reported appearances are somewhat reflective of workload, there seems to be a huge amount of unused capacity.

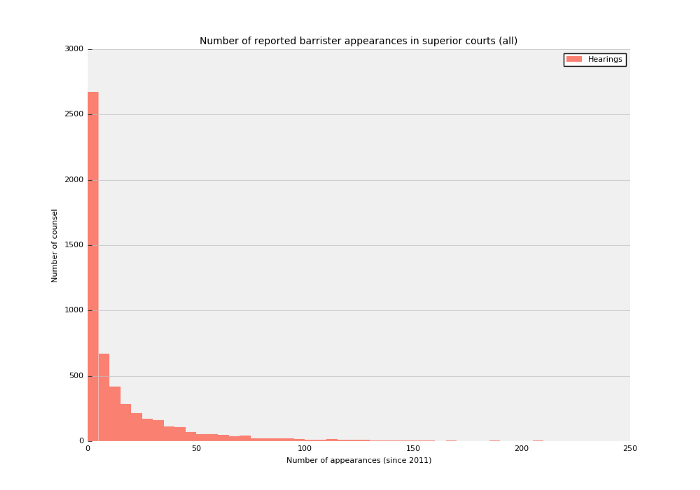

As is that case with barristers generally, very few female barristers have appeared more than 20 times in reported cases since 2011.[/caption] Excess capacity extends to the entire barrister pool, as shown in the following chart. Since 2011, very few barristers, whether male or female, have appeared in hearings that were reported. This reflects the status of the barrister job as the “most prestigious part time job in the history of the world”. It also reflects a potential flow on effect (probably intended) — if the number of briefs remain static, and a greater proportion of briefs go to women (who have capacity to take them on), then fewer briefs will go to men.

The vast majority of barristers have appeared less than 20 times in reported cases since 2011

Ultimately, assuming women have the excess capacity to take on more work, then supply-side problems would prevent solicitors from allocating 20 to 30% of briefs to female barristers.

Demand side: briefing practices of firms that frequently brief

Looking at the profile of barristers, of course, only tells one side of the story. Limitations associated with the make up of the barrister pool are supply-side limitations. The other side is the demand side — even if there were no limitations in supply, would demand from those briefing barristers be such that the targets would be met? Answering that question is difficult, as it is impossible to determine whether current briefing practices are driven by the limitation in supply, or biases in demand. Nonetheless, let’s look at firms and their briefing practices.

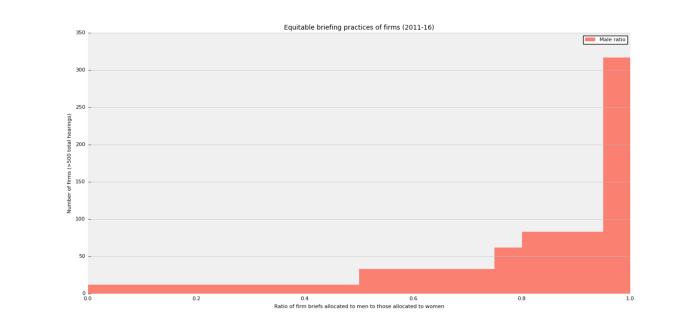

The majority of firms (>500 hearings in the past five years) nearly always brief males. Very few brief equally between genders.

Of the 660 firms which have briefed barristers in 500 or more reported hearings, over 300 of them briefed males for 95% of those hearings. There are a few explanations for this, none of which seem to be altogether convincing. First, there’s the supply problem. As explained above, it seems that there’s excess capacity — women barristers are able to take on more work. Another reason might relate to the fact that the data is limited to reported decisions in superior courts in NSW and Victoria. But then why are males preferred in those scenarios? Finally, it might be because there are many fewer female barristers of a certain seniority, such that there are no viable male alternatives. It’s possible, and without knowing the details of each particular brief, can’t be sure that it’s not a valid reason. But we know that over 13 per cent of barristers admitted 15 years or more ago are female, so there is some cause for skepticism. In any event, even if the reason is valid, the unavailability of experienced female barristers at certain levels of seniority and in certain areas of law supports the policy goal of ensuring greater representation across all areas of law.

Practical steps

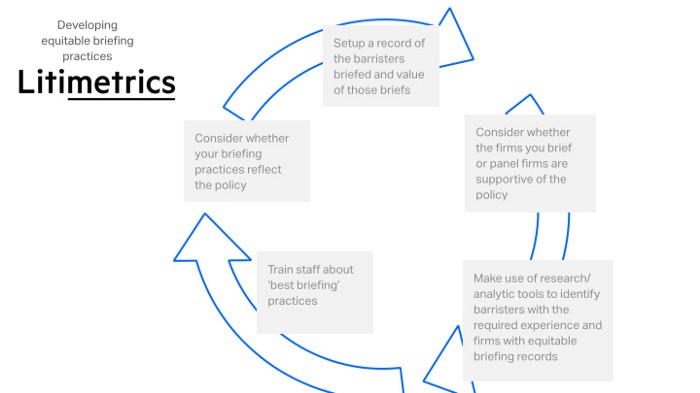

At some level, theorising about whether the goals are achievable is somewhat unhelpful. The policy goals have been set so focus should now turn to taking the necessary steps to achieve that goal. This is especially the case if the problems falls with those briefing barristers rather than with the supply of female barristers. This next section looks at the tangible steps you should take (many of which are taken from the Law Council itself).

Obviously, if you haven’t already done so, you should sign up to the policy. Signing up makes it clear to those both inside and outside your organisation that the organisation takes equality of briefing seriously. It empowers individual decision makers to take their own steps to achieving the organisational goals.

The next step is to take the time to consider what can be done within your own organisation to achieve the targets. The reporting obligations imposed on signatories will go some way to ensure that organisations do more than speak about change. Persons that make briefing decisions will have their personal favourites and their go-to barristers, so it will take a concerted effort to consider and brief others. You should consider whether your briefing practices reflect the policy — a first step may be to setup a record of the barristers briefed and value of those briefs. If there are a panel of legal service providers, then consider whether the makeup of the panel reflects the policy (eg, are the firms signatories?).

There are tools that will help decision makers identify credible alternatives. Litimetrics offers data about a barrister’s areas of expertise, their recent history of appearances, the firms that brief them and the barristers they appear with. The availability of these tools will make it easier for decision makers to educate themselves about alternatives. [Postscript: there were tools. Litimetrics was acquired in 2019 and no longer operates in Australia.]

For litigants and in-house counsel, consider working more closely with firms that have signed up to the policy. It’s often the case that firms nominate counsel to brief, so engaging firms whose interest align with those of your organisation will make identification of alternative counsel easier. Also consider engaging those firms with a track record of briefing female barristers. Litimetrics offers that data about firms and will help you identify the firms that will best help you meet the policy goals.

Finally, ongoing training of staff about ‘best briefing’ practices, will ensure that decision makers adopt practices that will promote achievement of the targets, and that the organisation fosters and encourages women barristers.